Groundwork (Photographs from Terra Nova National Park), 2008

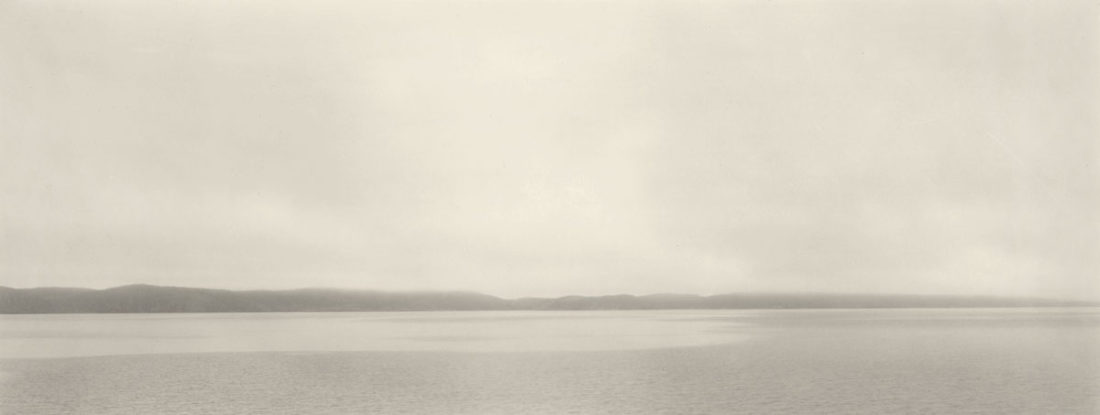

Groundwork is a series of photographs made during the month of June, 2008, when I was co-artist-in-residence (with my wife, poet Amanda Jernigan) at Terra Nova National Park, on the eastern coast of Newfoundland. Compared with the famous and dramatic landscapes of Newfoundland’s other national park, Gros Morne, Terra Nova’s is a landscape of subtlety and delicacy. The park occupies a coastal boreal forest arrayed across old, eroded mountains that are intricately riddled by sounds, coves, islands and bays. While much of the park comprises the expected web of trails, campsites, and look-outs, a great deal of the park’s importance involves its aquatic “landscape” and the rich life of the littoral zone.

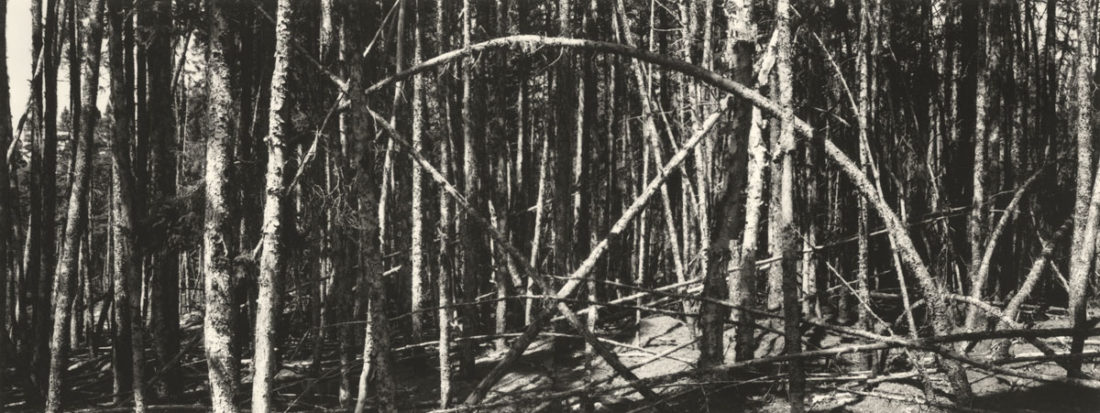

As is the case with many protected areas, some of the forests of the park were over-mature, a legacy of the human intervention of conservation practices. During our residency, we talked with wardens who were testing different techniques (trying to find the safest) of setting a forest on fire, intentionally. Because forest fires had been so effectively prevented, old trees were falling over and in the case of some species, new ones could not grow without the help of fire. The black spruce for instance, is serotinous, needing an external environmental factor — fire — to propagate. We also saw a large, fenced-off area in one forest, a moose exclusion zone, intended to keep the animals out, in order to suggest what the forest might have looked like before their arrival. (Moose are not native to the island, but were introduced in 1878 and 1904 from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia).

These two examples of interventions were indicative of the ongoing experiment of humans intentionally managing a wild-land. In the attempt to preserve, or conserve, what natural forces are stifled, and which are not? Does the outcome become a balance, or an imbalance, and how do plants, animals, and other natural factors respond to our interventions?

We were invited to go by boat to spend three days at Park Harbour, a remote wardens’ cabin: we were dropped off there by park staff, and picked up — early, as it happened, due to incoming weather. We were informed that this was a site where a “prescribed” burn was set to take place, shortly after we left. As a result, our relationship with this forested bay became charged; the place took on a preemptively lamentatory feel, as we knew that all we saw around us would cease to exist — or rather take on a completely different form — within a week. Indeed, we would be among the last members of the public (non-park employees) who would set eyes on this forest before it burned to the ground.

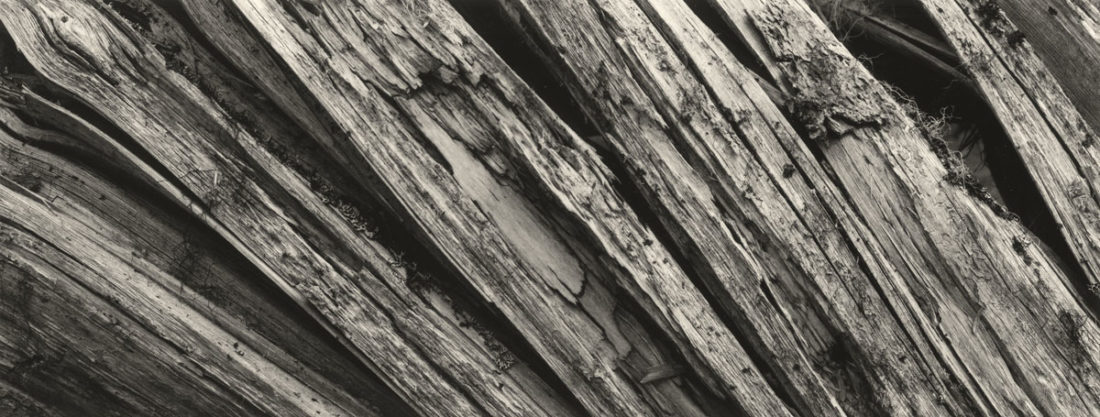

The photographs that comprise Groundwork became an act of close observation — both at a distance and in close-up — of the details of the place, both the rock-solid and the ephemeral; and an exploration of how human intervention, either intentional or accidental, might be evidenced in an apparently completely natural environment.

The series Groundwork consists of thirty-six images and is printed in two sizes. Black-and-white contact prints (4” x 10”) are toned silver gelatin prints on fibre-based paper. Colour contact prints (4” x 10”) are traditional c-prints. All images are also printed as 14” x 36” archival inkjet prints on rag paper. Both sizes are printed in an edition of five with one artist’s proof.