This Is My Song, 2017

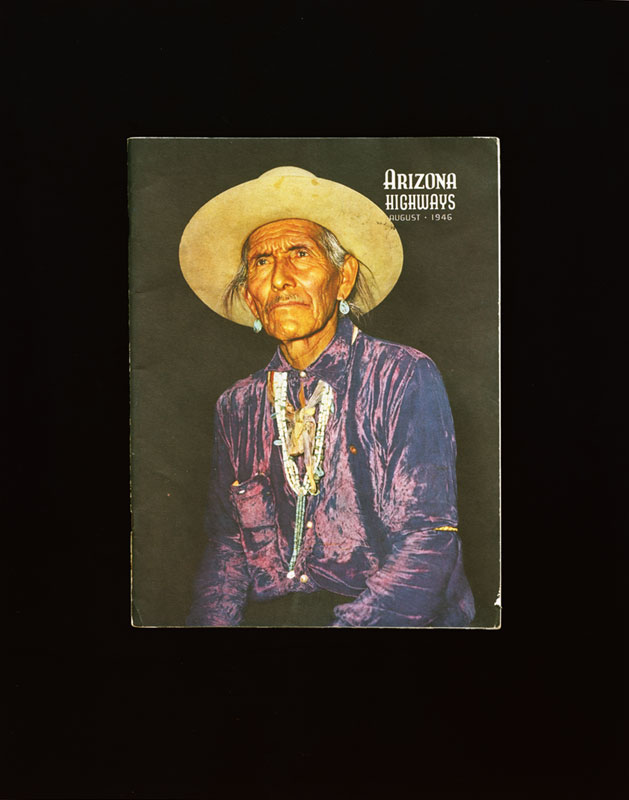

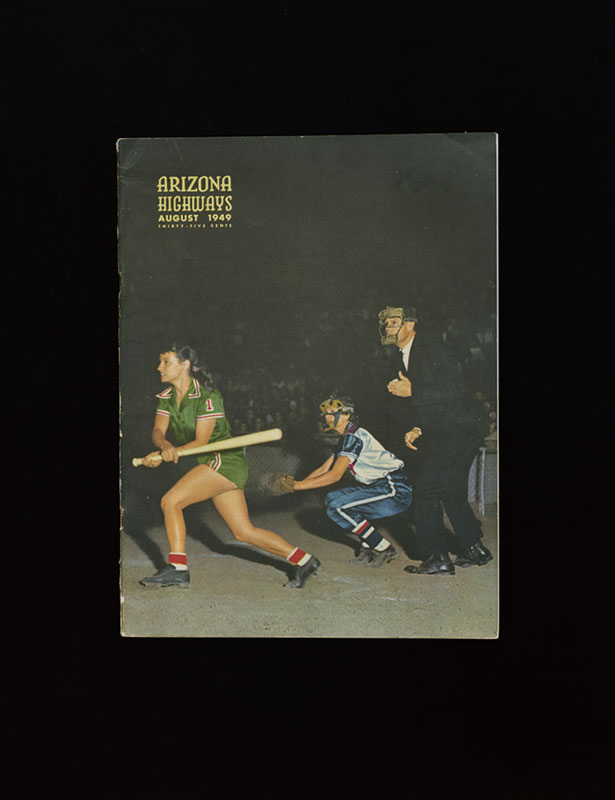

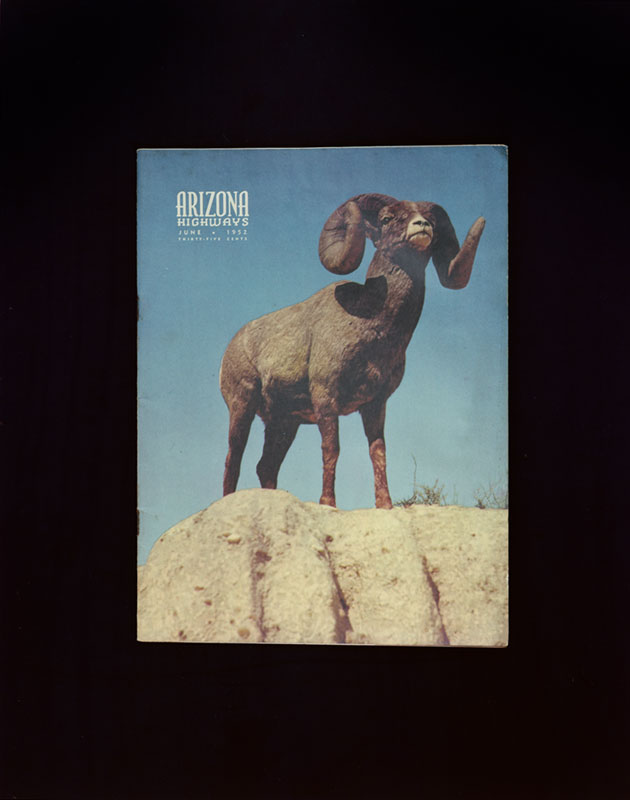

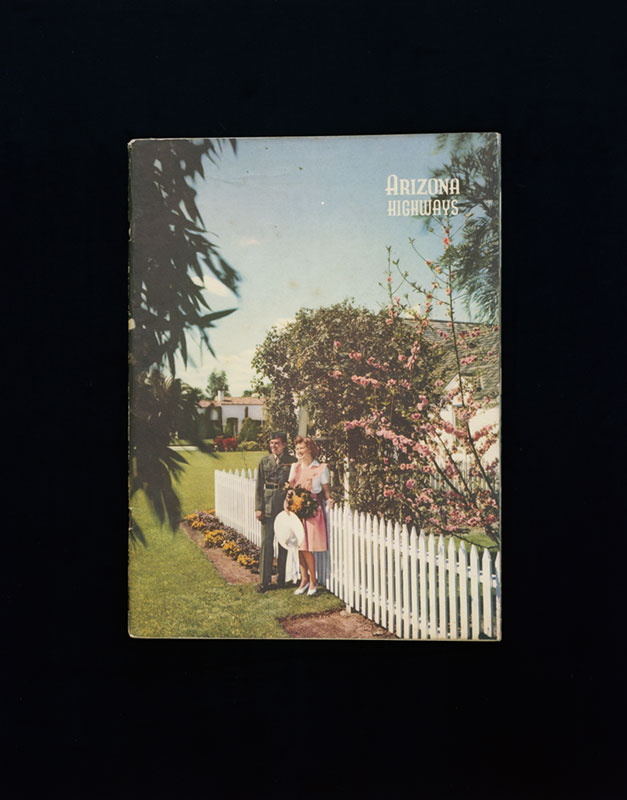

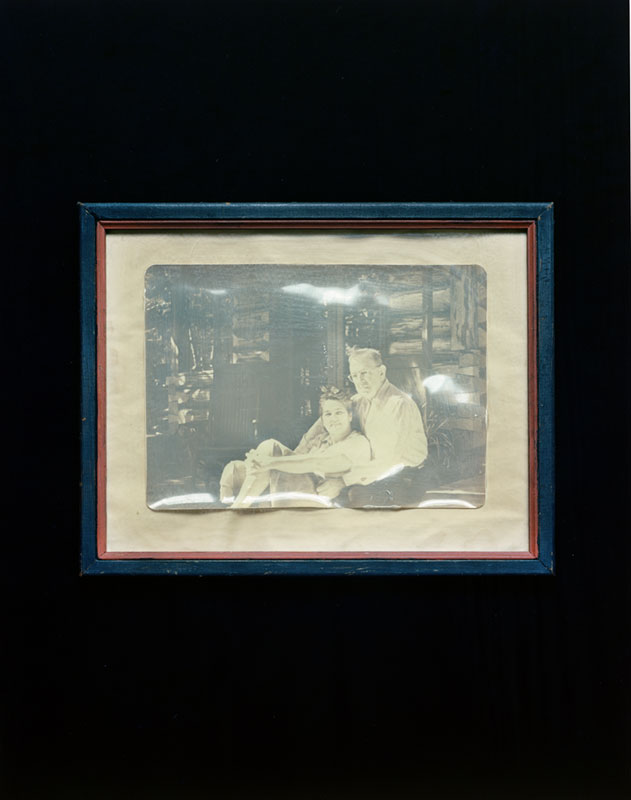

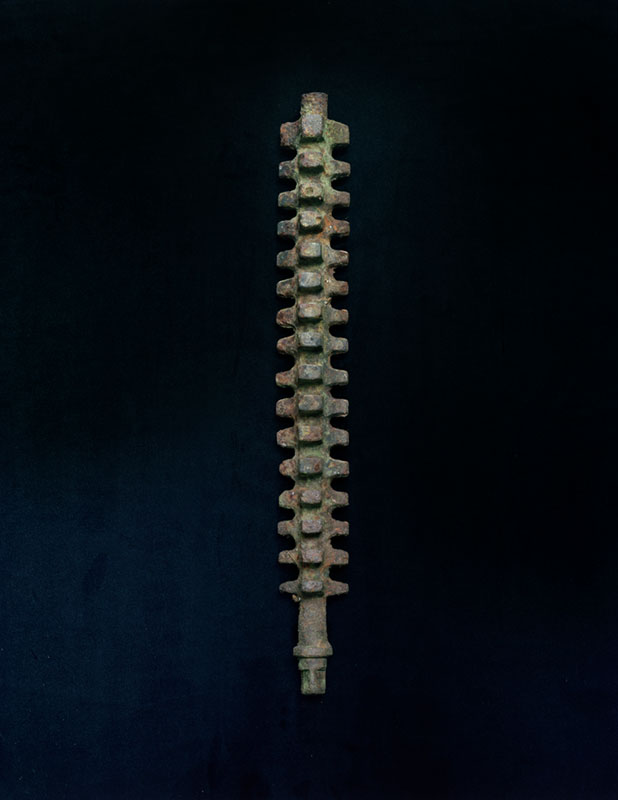

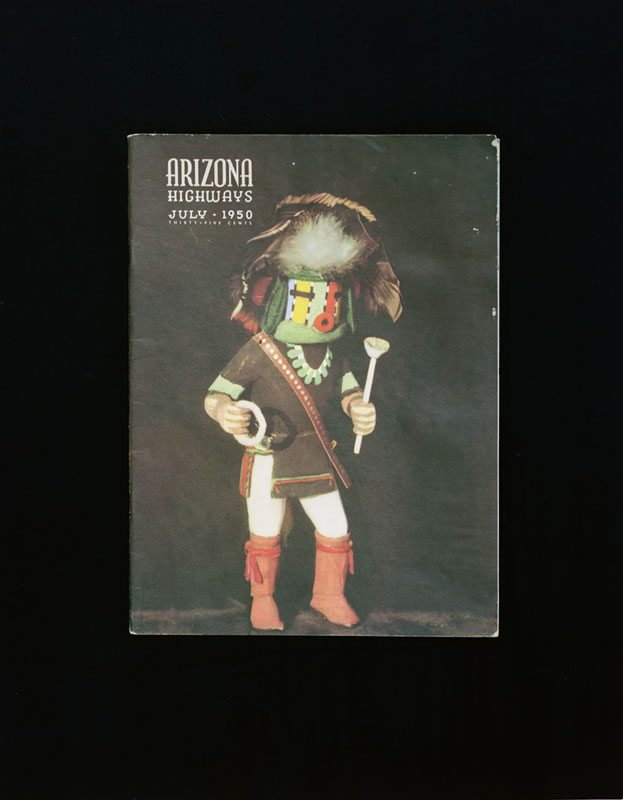

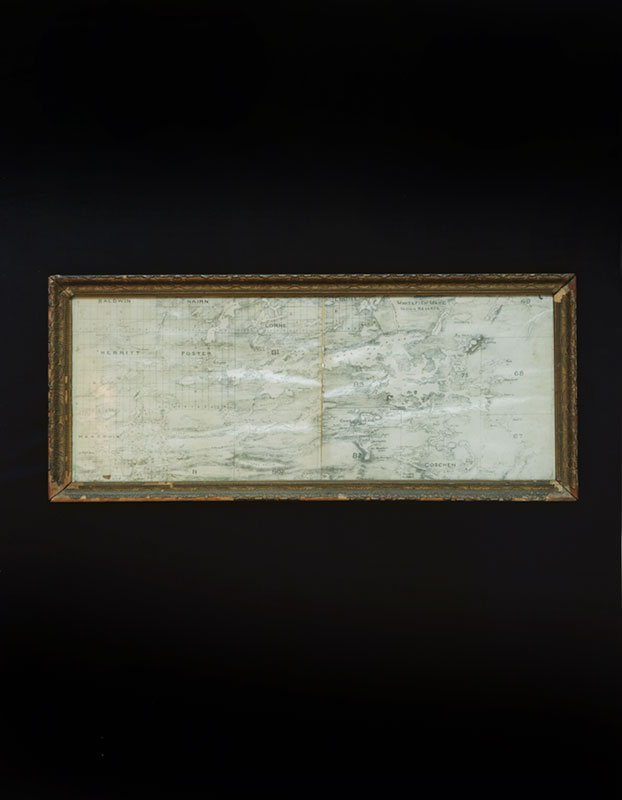

I never met my maternal great-grandfather — our lives missed one another by nine years. He was an American mining engineer who went to Sudbury, Ontario, working for the International Nickel Company (INCO) in the early 1930s. While there, he and his wife bought a piece of land on a newly-opened lake and built a cabin that has become a sanctum for my family. Like me, he had two sons, about the same age apart. I wanted to know more about this man. A great deal of his character is obvious from the physical evidence he left in the form of the cabin and its contents — he built every stick of furniture, for instance. But, I wanted to know more. His life seemed like one well-lived, and I was fascinated by the positioning of his life in the broader contexts of history and geography. Born in Rochester, NY, he went west with his family when he was a young boy, riding on the coattails of America’s “Manifest Destiny.” There was a too-late attempt to find gold in the Klondike. Then he came North to help mine the nickel that would make the steel that, in-and-around the Second World War, would create both tremendous growth and horrendous destruction. And he was fixated on the American Southwest, a world in which he immersed himself mentally, until he and my great-grandmother could move there in retirement. They rode along in a second conquest to the Pacific Ocean, colonized this time not by the bullet, but by the Interstate, the motel, and the Cadillac.

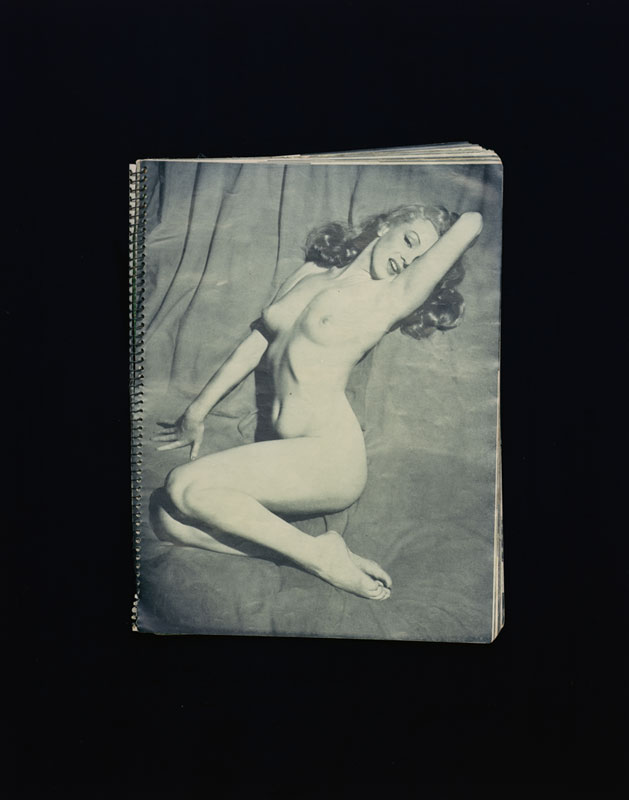

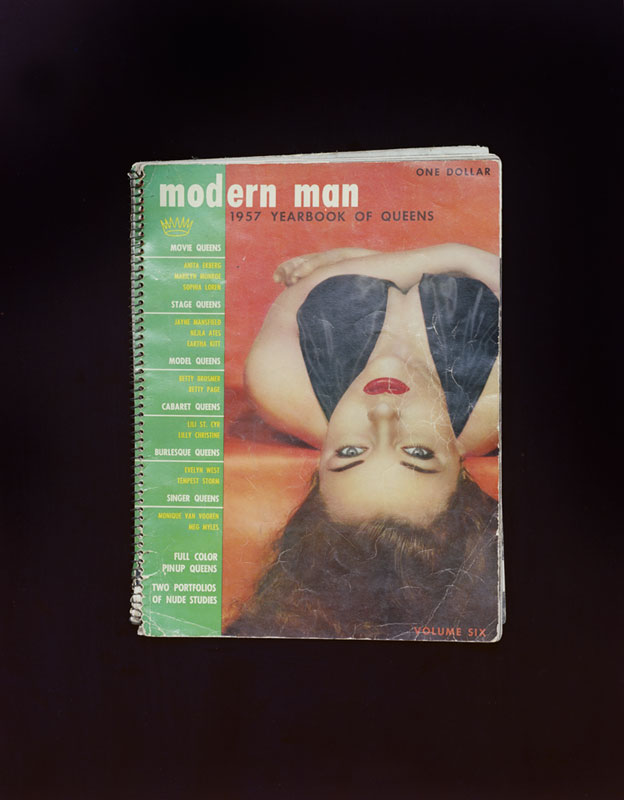

I gathered the iconic objects of his that I’ve come to know on summer trips to “Camp” — I’ve never missed a year. These objects, like touchstones, are so familiar to me that they’ve become part of the background. In order to see them anew, I isolated them on the black backdrop of a makeshift studio under the skylight of the sleep cabin and photographed them. They create a constellation in both a personal and a national mythology, the two of which, more often than not, overlap. This world of North American conquest/Western nostalgia, military righteousness, tools, physical work, machinery, baseball, drinking, pin-up girls, and family, is a fantasy — it is as seductive as it is problematic. These ingredients are the driving forces behind many of the problems we’re currently faced with, both societally and environmentally; they are aspects of an outmoded, once-promised dream. This man with whom I share many similarities, and on whose framework I formed much of my own sense of self, lived during a time nearly diametrically opposed to my own, and this series serves as both a bridge to, and a fence between, those two eras.

What are we to make of people we never knew, through their creations, desires, and material remnants? How do we forge bonds with family we never met? There is something important in the desire to want to know: that desire provides a kind of grit, a texture, on which sympathetic imagination may gain purchase.

During the time when I was making this work, my mother surprised me, procuring for me her grandfather’s typed memoir, a record that I hadn’t known existed. I opened the front cover of the three-ringed binder and read his title: This Is My Song.